Some thoughts on Batman

(Update: A revised version of this post has been published on Voyage. It can be found here.)

I recently wrote a piece for Voyage Comics & Publishing on a Thomistic ethical analysis of the mass fascination with superheroes evident in the last several years. In it, I argue that this fascination is rooted in the fundamental human desire for ultimate goodness or perfection. For it seems to me that no matter the character, superheroes are always depicted as those who wish to protect and preserve the common good in some way and in so doing strive to attain that perfection which we all desire.

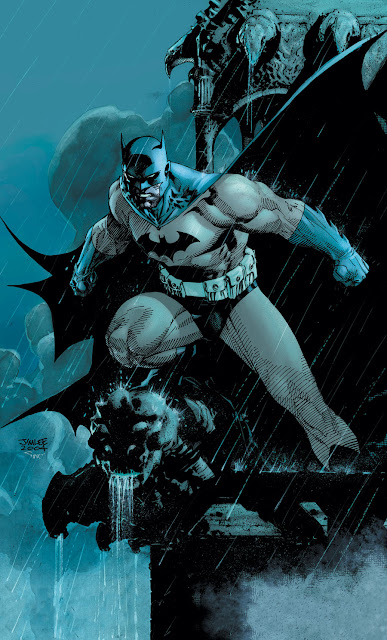

An interesting case in this is Batman. There are many reasons for this, but I would like in this post to focus on one which is probably mostly overlooked. Batman is quite distinct because, unlike many superheroes, he has a certain demeanor or attitude, a certain ethos, one might say, that one perhaps wouldn't expect. For, as I noted in the piece linked above, a couple of the names typically given to the ultimate goodness or perfection for which we as humans all long are "happiness" and "beatitude." We might expect, then, that someone who has achieved this level of happiness "more" than others, perhaps, (whatever that might mean) would "look" happier than others. I don't think that one necessarily needs a philosophical demonstration to see the evidence for this. Think of the most virtuous person you know--someone who instinctively and habitually acts for the good, i.e. is charitable, kind, generous, hospitable, doesn't indulge himself in things he shouldn't, always gives others their due, is never afraid to try to overcome obstacles that stand in the way of the good, and always seems to find the most reasonable means to attain that good. I would think that the person you have in mind is someone with a generally "cheery" attitude or disposition. This is the sort of disposition we can see in Superman or Spider-man (though, of course, they express this disposition in different ways). Or, at least, I would be surprised if you were imagining someone who was somewhat prone to anger, constantly serious, never smiles, somewhat gloomy, etc. (Of course, this may be the case if something bad had just happened to them, but that is irrelevant. A virtuous person would not be displaying such a disposition insofar as he is virtuous. Conversely, a vicious person may very well display the characteristics normally expected of a virtuous person. Ted Bundy, for example, was sort of notorious for not "looking" like or "appearing" like the "kind" of man who would commit the vile crimes he committed. But again, he would not "look" as such insofar as he is vicious. In fact, there are stories of him in which he seemed to take on an almost entirely different personality when he was abducting someone, as claimed here.)

However, those characteristics of a "gloomy" attitude are precisely the kind of that found in Batman, a superhero and, thus, a character we look to as an example of achieving some level of human perfection, as I argued in the article above. This sort of dark demeanor characteristic of Batman may or may not have been intended by his original writers and artists, but it is certainly the case now, and Batman is as popular as ever. One might then wonder: If we watch superheroes because of their level of achievement of human perfection, and that achievement is typically signified in human life by a certain disposition or charism, one that is, say, "cheery," why do we like Batman so much, who doesn't display that disposition at all? Does he still display the sort of virtue we typically hope to see in superheroes? If not, why are we still drawn to him? What is there in him to "look up" to?

Again, to be clear, I am in no way implying that there is a sort of essential connection between happiness and a certain "cheery" attitude such that a happy person must definitively (or something) have a cheery attitude or disposition. All I am pointing out is that there are certain characteristics we typically associate with happy people that are strikingly lacking in Batman. The right way to find the reason for this, I think, is to look at Batman's purpose and juxtapose it to someone else's which is clearly different than his, say, Superman's. Superman's purpose, from what I can tell, seems to be to protect his city from evil, to preserve the common good. His motivating force is established simply from the fact that he was raised by good Kansas parents who taught him to use his superpowers to assist humanity. Batman's purpose, on the other hand, seems to be primarily to cleanse his city and purify it, and only secondarily to protect it: "While Batman is focused on cleaning up Gotham from within, Superman has fought hard battles to keep Metropolis safe from outside forces" (from Andrew Garofalo's article from the same issue of mine in Voyage). Indeed, one of the constants in Batman story lines, whether in the comics, TV, or cinema, is that Gotham is wildly corrupt, riddled with criminality. But this "purifying" purpose presupposes that the city needs cleansing or purification, i.e. because it is filled with evil. For Batman's motivating force is from having witnessed that evil for himself at a formative age, on account of which encounter he resolved to eliminate that evil as best he could, a motivating force which is noticeably different from Superman's.

Thus, both Batman and Superman function as examples of achieving some level of human perfection, i.e. of what it means to do well as human, but in different ways. One way to understand this difference is by comparing it to the three stages of the spiritual life, which I will enumerate according to Aquinas's description (ST II-II.24.9), though it has been written about by many others. The three stages I'm referring to are in fact what Aquinas understands as the three degrees of charity: briefly, the first stage or degree is that in which the agent attempts to avoid sin and eliminate one's own moral evil; the second is that in which the agent attempts to add to the charity which they have attained to strengthen it; and the third is that in which the agent achieves union with God. The parallel with Batman and Superman I want to draw out is that, taking "the city" (whether Metropolis or Gotham) to be symbolic of the human soul, Batman, who is primarily focused on eliminating and removing evil, seems to be more representative of the first stage of the spiritual life, whereas Superman, who is focused on protecting and preserving the good, is representative of the second. (I'm hesitant to attribute the third stage to Superman's function, simply because that stage is so particular in its nature in the sense that it's so beyond human power. And I'm not sure what the third stage would look like in comic book form. If there is a story line out there, whether Batman, Superman, or otherwise, that would parallel well enough to it, my expectations would still be low with respect to accuracy. Perhaps when Spider-Man assumes the cosmic force or when Green Lantern attains the white ring would come close since in those moments Spider-Man and Green Lantern take on a sort of divine-like power. But even in those moments, such power is still meant to function as a sort of weapon against evil, and, hence, the union with that so-called "divinity" would have an end beyond itself, whereas true union with God is desirable for its own sake.)

I would argue, then, that what we like so much in Batman is that he is an example of what our relation to evil should be. When it comes to evil, Batman always takes it seriously. The level of corruption in Gotham demands such seriousness--Batman, or perhaps Gotham, rather, cannot afford anything less. He spends most of his time crime-fighting at night; hence he engulfs himself in the darkness, the privation of light, one of the perennial symbols for goodness and life (particularly for Plato). While enveloped in blackness, he attacks Gotham's sin with all of his strength and wit, bringing justice to the city, attempting to slowly and gradually bring it back to glory. And he never shies away from evil; he always faces it head-on. He looks it dead in the eye and spares it only little to no mercy (hence his "one rule," which of course may not work very well in the parallel I'm trying to draw out, but there are other independent things which are interesting about it).

The character of Batman thus expresses the proper attitude toward evil--not that all beginners in the spiritual life should always be or look "gloomy," but one cannot afford to let evil have its way even a little bit. It is as we have been taught: "If your right eye causes you to sin, pluck it out and cast it away from you; for it is better for you that one of your members should perish than for your whole body to be sent to hell. And if your right hand causes you to sin, cut it off and cast it away from you; for it is better for you that one of your members should perish than that your whole body go to hell" (Matthew 5:29-30). The message is clear: there is no room for sin in our lives, no room for evil to be entertained--it will only corrupt us and bring us closer to death. There is nothing about it that can be tolerated in ourselves. We must see it the way Batman does, or even better, as God does, and do everything we can to cast it out from our feeble and fragile lives.

Thus, both Batman and Superman function as examples of achieving some level of human perfection, i.e. of what it means to do well as human, but in different ways. One way to understand this difference is by comparing it to the three stages of the spiritual life, which I will enumerate according to Aquinas's description (ST II-II.24.9), though it has been written about by many others. The three stages I'm referring to are in fact what Aquinas understands as the three degrees of charity: briefly, the first stage or degree is that in which the agent attempts to avoid sin and eliminate one's own moral evil; the second is that in which the agent attempts to add to the charity which they have attained to strengthen it; and the third is that in which the agent achieves union with God. The parallel with Batman and Superman I want to draw out is that, taking "the city" (whether Metropolis or Gotham) to be symbolic of the human soul, Batman, who is primarily focused on eliminating and removing evil, seems to be more representative of the first stage of the spiritual life, whereas Superman, who is focused on protecting and preserving the good, is representative of the second. (I'm hesitant to attribute the third stage to Superman's function, simply because that stage is so particular in its nature in the sense that it's so beyond human power. And I'm not sure what the third stage would look like in comic book form. If there is a story line out there, whether Batman, Superman, or otherwise, that would parallel well enough to it, my expectations would still be low with respect to accuracy. Perhaps when Spider-Man assumes the cosmic force or when Green Lantern attains the white ring would come close since in those moments Spider-Man and Green Lantern take on a sort of divine-like power. But even in those moments, such power is still meant to function as a sort of weapon against evil, and, hence, the union with that so-called "divinity" would have an end beyond itself, whereas true union with God is desirable for its own sake.)

I would argue, then, that what we like so much in Batman is that he is an example of what our relation to evil should be. When it comes to evil, Batman always takes it seriously. The level of corruption in Gotham demands such seriousness--Batman, or perhaps Gotham, rather, cannot afford anything less. He spends most of his time crime-fighting at night; hence he engulfs himself in the darkness, the privation of light, one of the perennial symbols for goodness and life (particularly for Plato). While enveloped in blackness, he attacks Gotham's sin with all of his strength and wit, bringing justice to the city, attempting to slowly and gradually bring it back to glory. And he never shies away from evil; he always faces it head-on. He looks it dead in the eye and spares it only little to no mercy (hence his "one rule," which of course may not work very well in the parallel I'm trying to draw out, but there are other independent things which are interesting about it).

The character of Batman thus expresses the proper attitude toward evil--not that all beginners in the spiritual life should always be or look "gloomy," but one cannot afford to let evil have its way even a little bit. It is as we have been taught: "If your right eye causes you to sin, pluck it out and cast it away from you; for it is better for you that one of your members should perish than for your whole body to be sent to hell. And if your right hand causes you to sin, cut it off and cast it away from you; for it is better for you that one of your members should perish than that your whole body go to hell" (Matthew 5:29-30). The message is clear: there is no room for sin in our lives, no room for evil to be entertained--it will only corrupt us and bring us closer to death. There is nothing about it that can be tolerated in ourselves. We must see it the way Batman does, or even better, as God does, and do everything we can to cast it out from our feeble and fragile lives.

Comments

Post a Comment